Throughout its history, the American education system has served as a proxy for evolving cultural and political mores. In the Age of Reform, Horace Mann led a campaign to institute national public education as immigrants flooded cities, in part to encourage cultural assimilation and literacy among voters. Women lobbied for equal schooling opportunities prior to suffrage. One of the major landmarks of the Civil Rights Movement was the desegregation of Sumner Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. American art education has followed a similar path: perhaps the most prescient example is Black Mountain College, the celebrated birthplace of the American avant-garde, established in part by refugees fleeing Europe before the advent of World War II.

Today, we find ourselves in perpetual crisis. From rolling climate disasters to the present moment’s pandemic, our schools mimic our culture’s instability and distress. Universities across the country face increased budget cuts, both because of the pandemic and preexisting financial strains. A sluggish and uncertain job market is certainly of no help to enrollment statistics, if schools were once seen as a means to gainful employment. The student debt crisis accelerates as wages stagnate and costs of living increase. And for creatives, art education departments are more immediately imperiled and often the first cut in schools’ financial restructurings.

Among the most well-documented (and protested) examples of this trend was Cooper Union’s divestment from a model of free education into one subsidized by tuition. Around the same time that the #FreeCooperUnion movement emerged, seven members of the University of Southern California’s master of fine arts program dropped out in objection to fiscal restructuring plans and changes to their department’s curriculum. More recently, the Museum of Modern Art’s education department canceled contracts with freelance educators in response to last spring’s pandemic closures without clear plans for their reinstatement.

One moment of great disruption in American social history was the counterculture movement of the 1960s, which began in a period of upheaval much like our own. Alongside the popularization of free love came the creation of free schools, which were similarly positioned against the institutionalization of what were seen as oppressive norms (i.e., civil marriage and education sponsored by the state). Generally small and loosely organized at the grassroots level, these initiatives encouraged more liberal attitudes toward schooling than formal education could realistically accommodate. As a result, their curricula were more closely attuned to individuals’ particular needs: students were encouraged to follow their interests, and teachers served as facilitators instead of disciplinarians. Though they never fully integrated into the mainstream, these programs can be understood retrospectively as emergent utopias—microcosmic communities organized to liberate participants from the outdated values of a society that did not represent their own.

It is perhaps unsurprising then to find the free school movement emerging anew in this moment of great consequence and social disturbance. Though unaffiliated and located in opposite poles of the country, similar organizing strategies inform the pedagogies of No School at 2727 California Street, The Black School, and the School of the Alternative. I am inclined to believe that these schools suggest a collective response, however coincidental, to the failures of institutional education and the state of the art world today. What they offer, which follows, is a measured alternative.

Site Specificity and Community-Responsive Organizing

Unlike traditional schools, which are responsible for the education of hundreds, if not thousands, of individual students, alternative schools are uniquely structured to respond to the diverse needs of the communities they serve thanks to their intimate size. Their pedagogies also tend to correspond directly with the material and sociopolitical conditions of their specific geography.

At 2727 California Street in South Berkeley, California, neighbors and community members constitute a significant portion of the participants of No School, though artists from across the country travel to create work and participate in the space’s residency program alongside them. “Probably 80% of the kids just walk here,” says Lydia Glenn-Murray, an organizer at the school and residency. “It’s a really diverse neighborhood,” she continues. “It was a heavily Japanese neighborhood before internment and then turned into a mostly Black, African-American neighborhood after that, and then it was redlined.” This history has informed some of the educational initiatives they’ve planned, such as a project centered on studying the history of internment and making art in response to it. The space regularly hosts a free communal potluck, where residents, students, and neighbors who otherwise might not get to know one another convene.

School of the Alternative, initially named the Black Mountain School, sits quite presciently on the original campus of Black Mountain College, just a stone’s throw from Asheville, North Carolina. The school’s director, Heidi Gruner, acknowledges that many of the program’s first students were drawn to the school by its proximity to this historical predecessor. She notes, however, that while the project “burst out of a desire to create an alternative in the way that Black Mountain College created an alternative at that time,” the school’s organizers are now responding to the very different needs of our present moment. Their geographic positioning in the South significantly influences their organizing. Though most participants travel to North Carolina from New York, School of the Alternative offers an accessible alternative arts education program to Southerners in a region where few comparable options exist.

Also in the South, The Black School responds specifically to the needs of New Orleans’s Seventh Ward, where gentrification threatens to disrupt established Black communities in its surrounding neighborhoods. Though Joseph Cuillier and Shani Peters, the school’s organizers, are still in the process of acquiring land to build their schoolhouse, they are inspired by established precedents in the area, such as artist Willie Birch’s community garden and the Jones School, which was expressly built for the education of Black youth but became defunct in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Cuillier sees this project and its place in this neighborhood’s history as a “kind of space-keeping and activism in itself.” He acknowledges that historically “the Seventh Ward was this space for artisans and craftsmen and a free Black community,” and he is interested in “thinking about and imagining what the future of this space would look like for Black people.”

Experimentation and Experiential Learning

As a rule, alternative schools demand a degree of openness to their curricula, unlike traditional programs which adhere to strict syllabi regulated by state benchmarks and institutional standards. Students guide much of their learning in these schools by independently shaping the themes they investigate through experimentation and play. Learning in these settings is generally seen as a community-wide collaborative endeavor that departs dramatically from the lectures and seminars endemic to mainstream American classrooms.

In this tradition, students at No School at 2727 California Street are empowered to self-direct their creative exploration as a collective unit, which organizers facilitate and thoughtfully respond to. Intergenerational learning is at the center of this programming—children between the ages of seven and seventeen collaborate with community elders and visiting artists to realize the creative projects they engage. Age diversity “opens up a lot of play and wacky interesting things for everyone,” says Glenn-Murray, like inspiring new and expansive ways of thinking for all those who participate. In this setting, she has “felt so much liberation to experiment and be in a really open learning process instead of trying to prove something all the time in the way that the hierarchies of higher education and professionalization can [expect us to].”

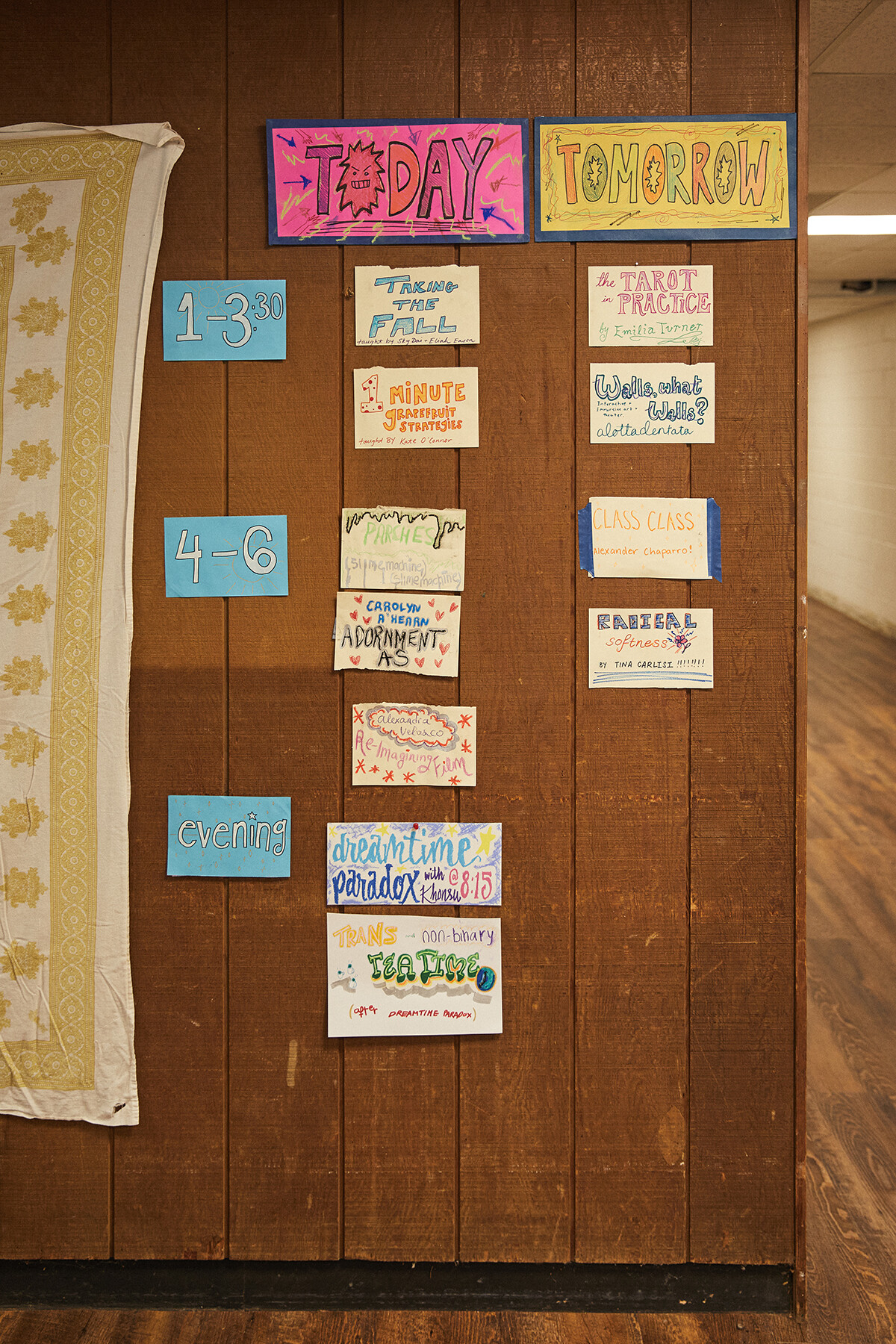

At School of the Alternative, many classes are also focused on an applied-practice methodology and feature diverse subjects, like collaborative weaving and do-it-yourself photography. The school’s curriculum is structured to ensure that class participation is interest-oriented and elective. No experience is necessary to attend. Discussion-based classes are conducted democratically; teachers might serve as moderators and architects of equitable discussion but never as dogmatists or sycophants. Students themselves are encouraged to lead classes of their own each session, which may be their first meaningful opportunity to do so in an organized setting. While at the school, Gruner assures me: “Folks quickly realize they have the power to learn anything they want to learn.”

The Black School begins their art-making workshops by asking participants two questions: What do you love about your community? and What do you want to change about your community? The responses they receive inform the topics they explore as a collective. Cuillier says this practice is influenced by the pedagogies of Paulo Freire and bell hooks, in which a “critical pedagogical approach” disrupts the norms of a “colonized classroom.” At The Black School, students are “expert[s] of [their] experience[s],” while facilitators simply “share the skills that [they] have.” Cuillier also acknowledges that their design apprenticeship program exists at the intersection of education and applied practice: students invited into the program learn practical design skills through creating work for clients, for which they are paid. This training prepares them to market these new skills in professional settings without the expenses entailed in pursuing a professional degree.

Disaffiliation from Art-World Politics

Alternative schools offer an unorthodox approach to norms in education and professional engagement by their very nature—this fact is self-evident and acknowledged in their name. These schools are divested from the exclusionary politics and practices that saturate art institutions and work to prioritize people who are traditionally excluded from them. They are concerned, above all else, with the communities they serve and producing real-world results.

At 2727 California Street, Glenn-Murray is able to focus on “beauty and freedom and joy” after “seeing the ways that those qualities of art-making got sucked dry when it got overly professionalized.” To exemplify this ethic, she recounts the story of when a friend in New York invited No School to take part in a gallery show on the Lower East Side: “We described the invitation and then one kid came in late and we asked, ‘Does anybody want to explain what she just missed?’ One of the kids shot his hand up and was like, ‘A gallery in New York City needs our help!’” Lydia admits it was refreshing to see someone whose “vision was unfiltered by his careerism.” Their sense of accomplishment comes from creating a space where art-making, is above all things, fun.

School of the Alternative accomplishes this same effort by disrupting the expectation of productivity that is normalized by most institutionally affiliated art schools. There is no requirement for students to make or finish work while on campus, and students’ success is not commodified by a grading system or institutional validation but is instead measured by their ability to grow as individuals and in connection to their community—all on their own terms.

In the course of his engagement with School of the Alternative, as both a student and teacher, Luan Sherman, now a member of its board, felt himself “detaching from a lot of ideas around value and labor as an individual.” He notes that, unlike in the art world, the students and faculty of School of the Alternative are not in competition with one another. The experience at the school “just flattens and deflates all of the things that the art world tells you you’re supposed to be: self-involved, an individual, totally not reliant on any help from anyone, wealthy. It pops all of those ideas. They’re not necessary in the culture that we’re trying to create,” he explains.

The Black School’s relationship to the art world is expressly non-adversarial: the school’s design firm launched at a show at The Block Gallery, which was supported by the Bronx Museum of the Arts, and Peters and Cuillier participated in a residency for the project at the New Museum in 2018, which resulted in a subsequent exhibition. In spite of these experiences, Cuillier acknowledges that these settings can be spaces of “white supremacist workings” and “hyper-capitalist politics” that are often alienating to Black artists. In building The Black School, Cuillier and his partner hope that they can create an alternative to these institutions that champions the “knowledge and experience [of their] community too.”

Social-Emotional Learning and Nonhierarchical Organizing

Because the relationship between alternative schools and the communities they exist in are so tight-knit, they are organized with an ethic of care not found in most institutional settings. Alternative schools are meant to empower individuals: they disrupt the power dynamic between students and teachers, who take on roles more like that of coconspirators than followers and leaders. Outcomes are measured by community feedback and are often assessed according to principles such as pleasure, growth, and joy instead of the pass–fail binary. These schools account for the prospect that growth might be forthcoming, a possibility usually precluded by schools’ and universities’ standardized tests and degree requirements. Here, education operates as a system of mutual aid, which is a radical departure from present colonial and carceral models.

Glenn-Murray of 2727 California Street notes how the broad age range of participants in No School disrupts the power dynamics present in typical schools and provides space for “different qualities of leadership [to be] recognized and celebrated.” The results are often quite formative for students’ self-concepts. She explains: “A little kid can really model a way of approaching a project that might be really different for an older kid [so] they can drop some pretense and really get into it because this little kid is, and the older kid might have more stamina for it, [which] might inspire the little kid to keep returning to it because they see, ‘Oh, I can do this too!’” Frank Traynor, another organizer of No School, emphasizes that a central aspect of the school’s pedagogy includes “reflections and processing of the art process,” which allows for feedback that is, above all things, refreshingly humane. The community learns as a unit based on what they accomplish together.

The power of communal care is central to programming at School of the Alternative, too. Its board has come to learn that conflict resolution can be a space of learning for both organizers and participants alike, which has influenced the way its community is structured. Upon arriving, all participants are given a point person to provide emotional support, space for listening, and feedback about their experience of the program. Students, staff, and faculty also collaborate on a community agreement each week that sets the contractual basis for how they expect to treat one another and be treated. This document serves as a constitution of community standards and cultural norms that takes all participants’ perspectives into account and democratizes the collective’s accountability process. This approach stands in stark contrast to the carceral models of justice that infiltrate larger society and the disciplinary standards inspired by this system that mostly serve to exacerbate trauma and create conflict in traditional educational communities. “We are actively doing things differently,” Sherman says.

Because the structure of the school, like these community standards, is of such collective effort, there is an inherent fluidity in the responsibilities of students, teachers, and staff, and on any given day, one can easily move between one role to another. Sherman emphasizes that acknowledging that there are different ways to learn is key to the school’s pedagogy, too: “Most of our programming is created and presented by people who are really neurodivergent.” This opportunity encourages diversity of thought and champions alternative authorities than those most readily accommodated in academic settings.

The values that inform the organizing of The Black School are “Black love, wellness, and self-determination,” says Cuillier—themes that are intentionally expansive. Their organizing principles are informed by other “Black radical organizations and Black liberation movements,” he continues, which center the needs of their community in ways that are also strategic and specific. “We see this more as community education, so it will run like a community center with an educational emphasis—particularly art and activism.” The Black School plans to organize classes that are both creative and holistic and appeal to younger and older audiences alike; alongside art-making, “there will be a community garden, a small activity space where we do yoga, [and] potentially self-defense classes,” he says. And because participatory input is so central to their organizing principles, there is space in their pedagogy to realize other needs and interests as their community suggests them, too.

Disrupting Economic Norms

A large obstacle alternative schools face is fiscal sustainability, which their traditional counterparts also struggle with. But unlike mainstream education programs, alternative schools seek to shoulder the burden of economic solvency so that their students don’t have to. Despite economic barriers, equity and access are of utmost priority to these organizers and inform how each school’s financial models are realized and maintained.

At 2727 California Street, all programming is free and residents are paid for the time they spend at the space. Any donations are couched by the invitation to “pay what makes sense for you,” which organizers acknowledge may very well be nothing. Because they do not ask people to prove what they can and cannot afford, their community “ends up being a pretty broad range culturally and socioeconomically,” says Glenn-Murray. She admits that she has “had to unlearn a lot of [her] own capitalist training” as a result of her experience organizing No School: “It doesn’t make sense in capitalism the way that we’ve been doing this.” Previously they were dependent on funding from the Hellerstein Foundation to subsidize the programs’ costs, but they are now exploring new means of supporting themselves without this backing’s guarantee, such as grant-writing and Patreon, and they continue to draw income from their shop, which sells art projects produced at the residency and No School.

School of the Alternative does charge students $400 a week to attend, but all proceeds go toward food and lodging, a PO Box, their website, a Zoom account, and minimal advertising. All of their organizers are unpaid. Scholarships are available to offset the cost of attending, and they are working toward acquiring enough funding to offer tuition on a sliding scale to half of all students. Teachers are paid a nominal fee for their time—less than $100 a week on their current model—but this offering is a contribution made in good faith with the understanding that it will increase as more funding flows in.

Reaching financial stability and economic equilibrium has been a journey for the program, which was initially founded in austerity. “The first few years, we were running on steam. We didn’t have the money really to start this. We were so in the negative that we paid our bills with a $0 balance,” Gruner says. Now, like 2727 California Street, they crowdsource funding on Patreon and are beginning to pursue grant writing, but as a relatively new initiative, they are just beginning to meet the eligibility requirements for many funded opportunities.

Gruner admits that it’s hard to ask for money because doing so inhibits access, but she concedes that she “wouldn’t be doing this work if part of it wasn’t working toward removing that barrier.” She dreams of one day being able to pay all participants and acknowledges that the compounding costs of travel, missed work, and related expenses all inhibit everyone who wants to from realistically being able to attend.

The Black School is funded through contributed revenue, like grants and donations, and money earned from their design firm. Cuillier believes that this financial model allows the school to “be more independent” and “self-reliant” in their pursuit of sustainable and responsible growth than they would be if they were operating under a model that was totally dependent on institutional support and nonprofit intervention. “If somebody’s dangling a check, and with it you can operate and without it you can’t operate, that’s not much of a choice,” he explains. Self-sufficiency ensures that capitalism doesn’t put them in a position of conflict with their values, which institutional support can sometimes do.

Invited students are free to attend classes and workshops without the expectation of a financial contribution, and some students will be paid for their time spent at the school, such as in their design apprenticeship program. All teaching artists will be paid for their labor, as well. “I think being realistic is important,” Cuillier says. “Our students … are impoverished. Our communities are economically oppressed. We have to think about money as a part of the school for the school to be successful.” He believes that inequitable economics are a major “issue with our schools and socially relevant education” today.